News from Maison de la Gare

A Volunteer's Cultural Awakening

Tweeter

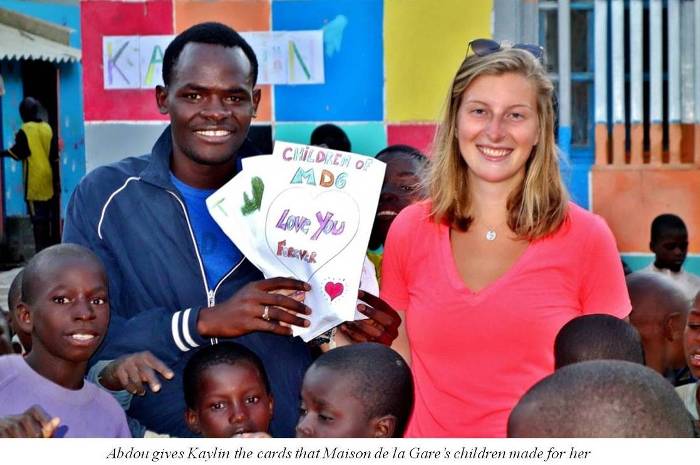

Kaylin Zimmer, American volunteer with Maison de la Gare

Kaylin studies economics at

Seattle University, specializing in International Economic Development. Coming

from Anchorage, Alaska, she has always loved to travel and fell in love with

Africa after her first trip in Malawi in 2013. Ever since, she has been

looking for a way to return while doing something meaningful. The opportunity

to intern with Maison de la Gare was a no-brainer, a chance to practice French,

return to a continent she loves and gain meaningful experience while making a

difference.

first trip in Malawi in 2013. Ever since, she has been

looking for a way to return while doing something meaningful. The opportunity

to intern with Maison de la Gare was a no-brainer, a chance to practice French,

return to a continent she loves and gain meaningful experience while making a

difference.

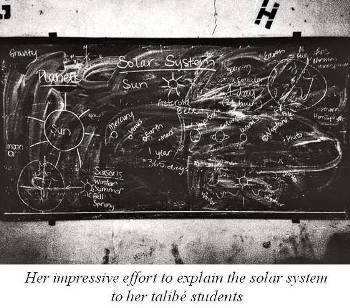

Kaylin’s work in Saint Louis includes helping to develop the system for

monitoring and tracking the boys who come to Maison de la Gare’s centre, in

addition to teaching English classes to older talibé children, helping in the

infirmary and much more.

In this report, Kaylin reflects on what she has learned working with Maison

de la Gare and the talibé children.

“As my time here draws near to a close, I’ve begun to realize (and to

try to come to terms with) that, when working as an outsider in a foreign

country,  there are some things that simply cannot be done.

there are some things that simply cannot be done.

Perhaps most glaring has been the simple fact that one cannot expect work

to be carried out in the same way as it is at home. One of the differences

I’ve noticed working here is that people put life before their work. If

there’s a baptism, a funeral, they’re too tired, their child got momentarily

lost (all things that I’ve heard from various people), these are the things

that come first. Baptisms and funerals are attended, they rest, and they

find their child and spend time with them. As a result, the efficiency and

diligence I am used to tend to go out the window. This relationship between

life and work is one I think many people and nations struggle with. I think

many Senegalese are still working out how to work in a country on the verge

of development,  yet with a subsistence lifestyle not so far behind them.

I’ve learned valuable lessons in patience and persistence, as both are

necessary to yield long-term results.

yet with a subsistence lifestyle not so far behind them.

I’ve learned valuable lessons in patience and persistence, as both are

necessary to yield long-term results.

Also interesting and challenging has been my experience as a white, agnostic

young woman coming from a country where none of this is out of the ordinary

and women’s rights are (relatively) progressive. Working for an organization

like Maison de la Gare, that deals so intimately with some of the deeply

religious Muslims in Senegal, it’s impossible for me to understand the

nuances and complexities of the Islamic faith, which in turn limits how

helpful I truly can be in tasks such as implementing our census of the

begging talibé children of Saint-Louis. While to me it may seem relatively

simple,  dealing with the marabouts here is sensitive both due to the fact

that they want some benefit for them if we expect them to give us verifiable

information, and that they may understand that some of what we do at Maison

de la Gare may undermine their power as many of them are exploiting the boys

we are trying to save from exploitation.

dealing with the marabouts here is sensitive both due to the fact

that they want some benefit for them if we expect them to give us verifiable

information, and that they may understand that some of what we do at Maison

de la Gare may undermine their power as many of them are exploiting the boys

we are trying to save from exploitation.

In a country where religion is paramount and some religious leaders benefit

from the mistreatment of children, and where women are seen less as agents

of change and more as objects to be admired, adored and responsible for a

household, it’s been challenging to find where I can truly have an impact

beyond the doors of the center. Part of what I’ve realized is that, even

if the best I do is get to know the boys, teach an English class that many

talibés desperately want to attend and help where the organization needs

help, that is enough. Though I have been helping with the register and the

census, the  times where I feel most valuable are in my interactions with

the friends I have made here, both young and old.

times where I feel most valuable are in my interactions with

the friends I have made here, both young and old.

And, of course, what affects everything I’ve mentioned and more is the

challenge of working in a country that speaks my second language, with an

unfamiliar accent, and more commonly speaks a language I speak none of at

all. Although this is certainly something for which I take responsibility,

as I knew where I was going, and although I expected French to be more

commonly spoken, I was aware that Wolof was the unofficial language. It

does pose a challenge when it comes to understanding all of what’s

happening around me. I miss out on conversations and, even during meetings

where I am present, they often begin in French and then digress into a

French-Wolof hybrid.  Although between my limited Wolof, my French and my

questions I always understand the key takeaways of the meetings, I still

miss the nuances of why one idea may not work, or why something else is

better. When these involve the marabouts and the obstacles involving them

and their faith, it often becomes even more confusing as I struggle to

grasp the weight that religion has for many people.

Although between my limited Wolof, my French and my

questions I always understand the key takeaways of the meetings, I still

miss the nuances of why one idea may not work, or why something else is

better. When these involve the marabouts and the obstacles involving them

and their faith, it often becomes even more confusing as I struggle to

grasp the weight that religion has for many people.

My time here has been a cultural awakening, truly. Before leaving home,

my fellow interns and I were told repetitively to acknowledge that we were

going somewhere we were unfamiliar with, into an organization that has been

doing their jobs for long enough to likely know better than us, and that we

should be open to understanding their perspectives. While all of this has

been true and I have learned a lot, I feel that most of what I have learned

has been incredibly humbling, not because it turns out I know very little

academically or work-specific but because I know so little about the

culture and the importance of religion here. Not understanding the

strongest values of the people limits my ways of understanding how to best

work with or around them.

learned a lot, I feel that most of what I have learned

has been incredibly humbling, not because it turns out I know very little

academically or work-specific but because I know so little about the

culture and the importance of religion here. Not understanding the

strongest values of the people limits my ways of understanding how to best

work with or around them.

My stay in Senegal has been my own sensitivity training, becoming sensitized

to how the beliefs of the people we are with affect how we can and cannot

make progress. I think this is a lesson that I need to continue to learn,

as there are still many times when I get frustrated with the rate at which

projects are accomplished. However, I am also learning how to know when my

way may be better, and how to demonstrate to others why I do things the way

I do them and why they may benefit from this as well.”