News from Maison de la Gare

The Trip of a Lifetime

Tweeter

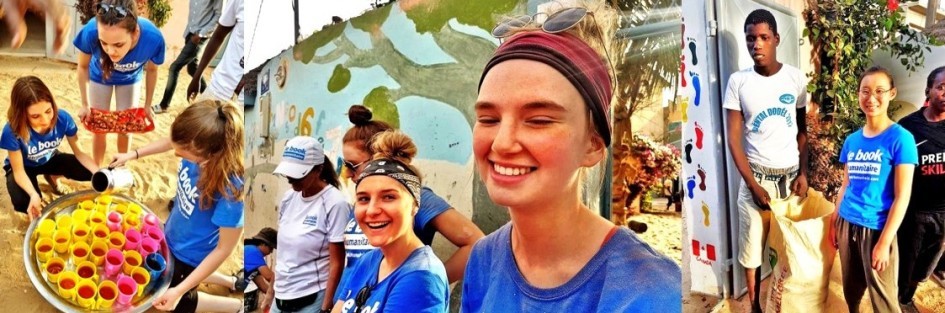

Le Book Humanitaire’s mission to Maison de la Gare in Saint-Louis, Senegal

"When we left, which

was unbelievably sad, I was deeply moved by the appreciation of the young

talibés, by their smiles.  They had prepared a song for us," recalls Daphné

Deschambault, a secondary-five student at Polyvalente Saint-Jérôme in Quebec.

They had prepared a song for us," recalls Daphné

Deschambault, a secondary-five student at Polyvalente Saint-Jérôme in Quebec.

Twenty students from the Polyvalente and two teachers, Alain Dionne and

Isabelle Levert, joined Rachel Lapierre, the founder of Le Book Humanitaire,

to take a flight to the far reaches of the earth, to Saint-Louis in Senegal.

It’s a poor and overcrowded city where there are talibés confined in daaras

(the name given to Koranic schools). A talibé is a young boy from a poor

family who has been entrusted to a Koranic teacher (a marabout) and who is

expected to perfect his religious knowledge. "Do not look for girls," says

Geneviève Bédard, another participant, "it is total inequality between the

sexes in Senegal."

The fate of the talibés could not be more tragic. "It’s enough to fall

into the hands of a bad marabout," says Émile Éthier, still proud of his

experience building a concrete floor in a daara. Indeed, these naive

children, virtual slaves, too often have to beg and take care of domestic

tasks to enable their religious master and his family to live well.

Unhealthy conditions,  filth, poverty, disease, malnutrition. So many

difficulties, but these boys live without it ever suppressing their

proverbial smile, their thirst for discovery and their faith in existence.

filth, poverty, disease, malnutrition. So many

difficulties, but these boys live without it ever suppressing their

proverbial smile, their thirst for discovery and their faith in existence.

The mission of the non-profit organization Le Book Humanitaire is to bring

about positive change in such situations.

Culture Shock

To help, to want to share one's knowledge, one's humanity, is one thing.

To do this in a situation where the reality is so different from our

cultural points of reference is something else. "Children here fight for

food ; we throw it out," says Genevieve. Daphne adds: "When I realized

that not all the children were going to receive the food we had prepared

for them, I was really upset."

Children who reach out their hands, wanting food but caught in the

deprivation imposed by the Muslim Ramadan. This reality opened the

Polyvalente students’ eyes. They felt pampered and privileged. "Young

talibés are happy and grateful for life. We have everything, yet we are

materialistic and dissatisfied. It changed me. I can’t wait to leave on

another trip" says Justine Ouellet, her eyes sparkling.

In a country where a man’s wealth is measured by the number of goats he owns,

the cultural differences are obvious. When the number of television antennas

on a Senegalese house indicates the number of women a polygamous man has

married, the culture shock is total.

In a country where a man’s wealth is measured by the number of goats he owns,

the cultural differences are obvious. When the number of television antennas

on a Senegalese house indicates the number of women a polygamous man has

married, the culture shock is total.

The Polyvalente students, including

Émile among others, have changed their personal habits. "In this context,

seeing such poverty, I realized that I prefer to give rather than receive,

especially to those who are poorer. Since my trip I am more sensitive to

the misery of others, to the homeless as well. I even finish my meals!” he

exclaims thoughtfully.

Many Tasks

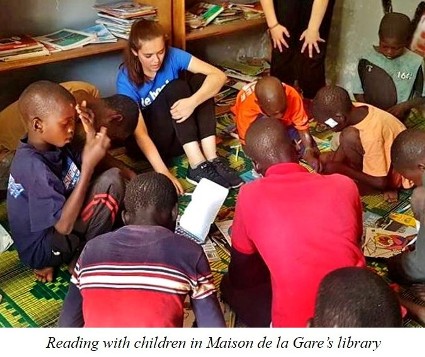

Several work projects organized by Le Book Humanitaire gave students a chance

to develop new skills. Some students were introduced to the world of basic

health care in Maison de la Gare’s infirmary. "I learned

to bandage, wash

and disinfect wounds and to take blood pressure," says Geneviève Bédard,

while one of her companions adds that some young children seek care only for

the sake of being comforted.

to bandage, wash

and disinfect wounds and to take blood pressure," says Geneviève Bédard,

while one of her companions adds that some young children seek care only for

the sake of being comforted.

Other students helped by painting a beautiful mural at the entrance to the

center, and by beautifying the garden with colorfully painted discarded tires.

"I loved the contact with the children while we were working on these

projects," says Justine.

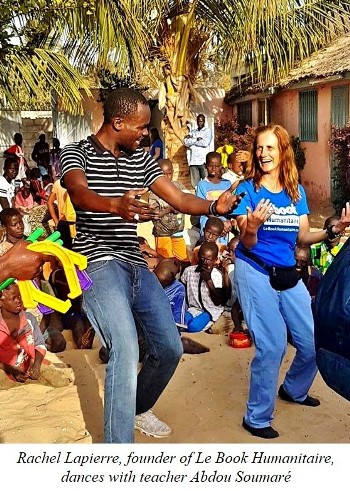

Isabelle Levert, teacher and trip organizer, summarizes their experience on

their last day: "After a little shopping, part of our last day at Maison de

la Gare, we finished the mural, distributed school supplies and educational

games, and prepared  and served the meal (the only one of the day for most of

the children). And, we distributed maple syrup candy to everyone, along with

caps and bracelets made by the students. We were warmly thanked,

individually, by the children and by Maison de la Gare’s staff members. We

are now part of their big family. The goodbyes were very difficult for some.

But, to cheer up the troops, we danced and sang with them.”

and served the meal (the only one of the day for most of

the children). And, we distributed maple syrup candy to everyone, along with

caps and bracelets made by the students. We were warmly thanked,

individually, by the children and by Maison de la Gare’s staff members. We

are now part of their big family. The goodbyes were very difficult for some.

But, to cheer up the troops, we danced and sang with them.”

Isabelle continues: "I don’t know if I should be happy or sad. I am happy

because young students from Canada have left their studies, their families,

their work, their comfort zones to help the talibé children of Maison de la

Gare, and to better understand the causes of forced begging of the talibé

children of Senegal. But even more, we had the immense pleasure of working

with them. We truly hope that the bonds that have been forged will last

forever and that we can continue to be a vibrant network of young intellectuals

ready to work for a better life for the talibé children."

But beyond all these unforgettable memories, a doubt remains. The needy

glances, the powerlessness in the face of a society whose organization

escapes us. Through all this, Émile's wisdom offers hope. "The talibés

find happiness in all the little things," he says, comparing our attitude

to theirs.